Expertise is commitment coupled with creativity. Specifically, it is the commitment of time, energy, and resources to a relatively narrow field of study and the creative energy necessary to generate new knowledge in that field. It takes a considerable amount of time and regular exposure to a large number of cases to become an expert.

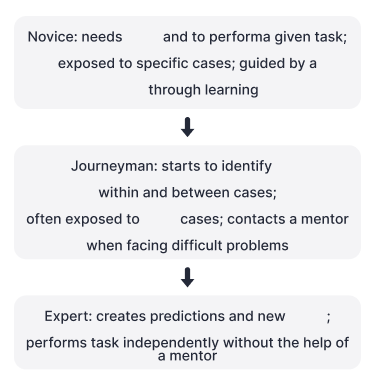

An individual enters a field of study as a novice. The novice needs to learn the guiding principles and rules of a given task in order to perform that task. Concurrently, the novice needs to he exposed to specific cases, or instances, that lest the boundaries of such principles. Generally, a novice will find a mentor to guide her through the process of acquiring new knowledge. A fairly simple example would be someone learning to play chess. The novice chess player seeks a mentor to leach her the object of the game, the number of spaces, the names of the pieces, the function of each piece, how each piece is moved, and the necessary conditions for winning, or losing the game.

In time, and with much practice, the novice begins to recognise patterns of behavior within cases and, thus, becomes a journeyman. With more practice and exposure to increasingly complex cases, The journeyman finds patterns not only within cases but also between cases. More importantly, the journeyman learns that these patterns often repeat themselves over time. The journeyman still maintains regular contact with a mentor to solve specific problems and learn more complex strategies. Returning to the example of the chess player, the individual begins to learn patterns of opening moves, offensive and defensive game-playing, strategies, and patterns of victory and defeat.

When a journeyman starts to make and test hypotheses about future behavior based on past experiences, she begins the next transition. Once she creatively generates knowledge, rather than simply matching, superficial patterns, she becomes an expert. At this point, she is confident in her knowledge and no longer needs a mentor as a guide she becomes responsible for her own knowledge. In the chess example, once a journeyman begins competing against experts, makes predictions based on patterns, and tests those predictions against actual behavior, she is generating new knowledge and a deeper understanding of the game. She is creating her own case, rather than relying on the cases of others.

The Power of Expertise

An expert perceives meaningful patterns in her domain better than non-experts. Where a novice perceives random or disconnected data points, an expert connects regular patterns within and between cases. This ability to identify patterns is not an innate perceptual skill; rather it reflects the organisation of knowledge after exposure to and experience with thou-sands of cases.

Experts have a deeper understanding of their domains than novices do, and utilise higher-order principles to solve- problems. A novice, for example, might group objects together by color or size, whereas an expert would group the same objects according to their function or utility. Experts comprehend the meaning of data and weigh variables with different criteria within their domains belter than novices. Experts recognise variables that have the largest influence on a particular problem and focus their attention on those variables.

Experts have better domain-specific short-term and long-term memory than novices do. Moreover, experts perform tasks in their domains faster than novices and commit fewer errors while problem solving. Interestingly, experts go about solving problems differently than novices. Experts spend more time thinking, about a problem to fully understand it at the beginning of a task than do novices, who immediately seek to find a solution, Experts use their knowledge of previous cases as context tor creating mental models to solve given problems.

Better at self-monitoring than novices, experts are more aware of instances where they have committed errors or failed to understand a problem. Experts check their solution more often than novices and recognise when they are missing, information necessary for solving a problem. Experts are aware of the limits of their domain knowledge and apply their domain's heuristics to solve problems that fall outside of their experience base.

The Paradox of Expertise

The strengths of expertise can also be weaknesses. Although one would expect experts to be good forecasters, they are not particularly good at making predictions about the future. Since the 1930s, researchers have been testing, the ability of experts to make forecasts. The performance of experts has been tested against actuarial tables to determine if they are better at making predictions than simple statistical models. Seventy years later, with more than two hundred experiments in different domains, it is clear that the answer is no. If sup-plied with an equal amount of data about a particular case, an actuarial table is as good, or better, than an expert at making, calls about the future. Even if an expert is given more spe-cific case information than is available to the statistical model, the expert does not tend to outperform the actuarial table.

Theorists and researchers differ when trying, to explain why experts are less accurate forecasters than statistical models. Some have argued that experts, like all humans, are inconsistent when using mental models to make predictions. That is, the model an expert uses for predicting X in one month is different from the model used for predicting X in a following, month, although precisely the same case and same data set are used in both instances.

A number of researchers point to human biases to explain unreliable expert predictions. During, the last 30 years, researchers have categorised, experimented, and theorised about the cognitive aspects of forecasting. Despite such efforts, the literature shows little consensus regarding the causes or manifestations of human bias.

Vì đối tượng là 'novice', ta biết thông tin cần đọc ở đoạn 2

Vì đối tượng là 'novice', ta biết thông tin cần đọc ở đoạn 2 Áp dụng Linearthinking để nắm main idea:

Áp dụng Linearthinking để nắm main idea: