Chairman:

We're very pleased to welcome to our special interest group today, Dr. Linda Graycar who is from the City Institute for the Blind. Linda is going to talk to us about the system of writing for the blind known as Braille. Linda, welcome.

Chairman:

Now we'd like to keep this session pretty informal, and I know Linda won't mind if members of the group want to ask questions as we go along. Let's start with an obvious one. What is Braille and where does it get its name from?

Dr. Graycar:

Well, as you said, Braille is a system of writing used by and for people who cannot see. It gets its name from the man who invented it, the Frenchman Louis Braille who lived in the early 19th century.

Chairman:

Was Louis Braille actually blind himself?

Dr. Graycar:

Well ... he wasn't born blind, but he lost his sight at the age of three as the result of an accident in his father's workshop. Louis Braille then went to Paris to the National Institute for Blind Children and that's where he invented his writing system at the age of only 15 in 1824 while he was at the Institute.

Chairman:

But he wasn't the first person to invent a system of touch reading for the blind, was he?

Dr. Graycar:

No - another Frenchman had already come up with the idea of printing embossed letters that stood out from the paper but this was very cumbersome and inefficient.

Chairman:

Did Louis Braille base his system on this first one?

Dr. Graycar:

No, not really. When he first went to Paris he heard about a military system of writing using twelve dots. This was a system invented by an enterprising French army officer and it was known as ' night writing' It wasn't meant for the blind, but rather ... for battle communications at night.

Chairman:

That must've been fun!

Dr. Graycar:

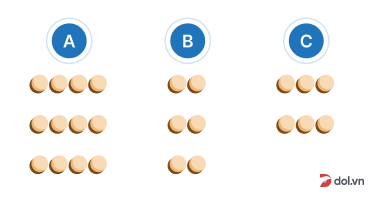

Anyway, Braille took this system as a starting point but instead of using the twelve dots which 'night writing' used, he cut the number of dots in half and developed a six-dot system.

Chairman:

Can you give us a little more information about how it works?

Dr. Graycar:

Well, it's a system of touch reading which uses an arrangement of raised dots called a cell. Braille numbered the dot positions 1-2-3 downward on the left and 4-5-6 downward on the right. The letters of the alphabet are then formed by using different combinations of these dots.

Student:

So is the writing system based on the alphabet with each word being individually spelt out?

Dr. Graycar:

Well ... it's not quite that simple, I'm afraid! For instance, the first 10 letters of the alphabet are formed using dots 1, 2, 4 and 5. But Braille also has its own short forms for common words. For example, 'b' for the word 'but' and 'h' for 'have' - there are many other contractions like this.

Chairman:

So you spell out most words letter by letter, but you use short forms for common words.

Dr. Graycar:

Yes. Though, I think that makes it sound a little easier than it actually is!

Chairman:

And was it immediately accepted? I mean, did it catch on straight away?

Dr. Graycar:

Well, yes and no! It was immediately accepted and used by Braille's fellow students at the school but the system was not officially adopted until 1854, two years after Braille's death. So, official acceptance was slow in coming!

Student:

I suppose it works for all languages which use the roman alphabet?

Dr. Graycar:

Yes, it does, with adaptations, of course.

Student:

Can it be written by hand or do you need a machine to produce Braille?

Dr. Graycar:

Well, you can write it by hand on to paper with a device called a slate and stylus but the trick is that you have to write backwards ... e.g. from right to left so that then when you turn your sheet over, the dots face upwards and can be read like English from left to right.

Dr. Graycar:

But these days you'd probably use a Braillewriting machine, which is a lot easier!

Chairman:

And, tell us, Linda. Is Braille used in other ways? Other than for reading text?

Dr. Graycar:

Yes, indeed. In addition to the literary Braille code, as it's known, which of course includes English and French, there are other codes. For instance, in 1965 they created a form of Braille for Mathematics.

Student:

I can’t, imagine trying to do maths in Braille!

Dr. Graycar:

Yes, that does sound difficult, I agree. And there's also a version for scientific notation. Oh and yes, I almost forgot, there is now a version for music notation as well.

Chairman:

Well, thanks, Linda.

Mình cần nghe xem Louis Braille bị mù ở đâu (Louis Braille was blinded as a child in his ... )

Mình cần nghe xem Louis Braille bị mù ở đâu (Louis Braille was blinded as a child in his ... ) Nghe thấy "he lost his sight at the age of three as a result of an accident in his father's workshop" (lost his sight = was blinded)

Nghe thấy "he lost his sight at the age of three as a result of an accident in his father's workshop" (lost his sight = was blinded)