CATHY:

OK, Graham, so let’s check we both know what we’re supposed to be doing.

CATHY:

So, for the university’s open day, we have to plan a display on British life and literature in the mid-19th century.

GRAHAM:

That’s right. But we’ll have some people to help us find the materials and set it up, remember – for the moment, we just need to plan it.

CATHY:

Good. So have you gathered who’s expected to come and see the display? Is it for the people studying English, or students from other departments? I’m not clear about it.

GRAHAM:

Nor me. That was how it used to be, but it didn’t attract many people, so this year it’s going to be part of an open day, to raise the university’s profile.

GRAHAM:

It’ll be publicised in the city, to encourage people to come and find out something of what does on here. And it’s included in the information that’s sent to people who are considering applying to study here next year.

CATHY:

Presumably some current students and lecturers will come?

GRAHAM:

I would imagine so, but we’ve been told to concentrate on the other categories of people.

CATHY:

Right. We don’t have to cover the whole range of 19th-century literature, do we?

GRAHAM:

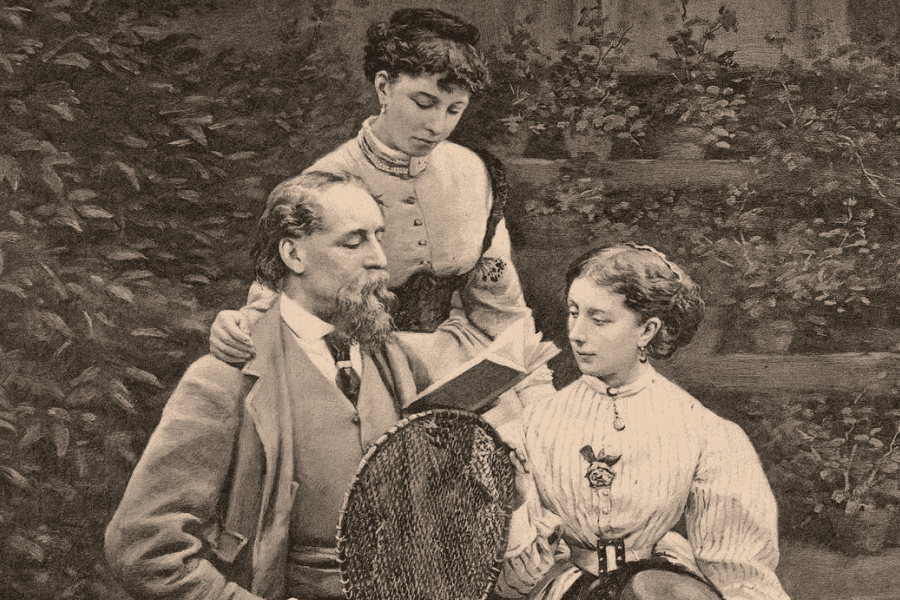

No, it’s entirely up to us. I suggest just using Charles Dickens.

CATHY:

That’s a good idea. Most people have heard of him, and have probably read some of his novels, or seen films based on them, so that’s a good lead-in to life in his time.

GRAHAM:

Exactly. And his novels show the awful conditions that most people had to live in, don’t they: he wanted to shock people into doing something about it.

CATHY:

Did he do any campaigning, other than writing?

GRAHAM:

Yes, he campaigned for education and other social reforms, and gave talks, but I’m inclined to ignore that and focus on the novels.

CATHY:

OK, so now shall we think about a topic linked to each novel?

GRAHAM:

Yes. I’ve printed out a list of Dicken’s novels in the order they were published, in the hope you’d agree to focus on him!

CATHY:

You’re lucky I did agree! Let’s have a look. OK, the first was The Pickwick Papers, published in 1836. It was very successful when it came out, wasn’t it, and was adapted for the theatre straight away.

GRAHAM:

There’s an interesting point, though, that there’s a character who keeps falling asleep, and that medical condition was named after the book – Pickwickian Syndrome.

CATHY:

Oh, so why don’t we use that as the topic, and include some quotations from the novel?

GRAHAM:

Right, Next is Oliver Twist. There’s a lot in the novel about poverty. But maybe something less obvious …

CATHY:

Well Oliver is taught how to steal, isn’t he? We could use that to illustrate the fact that very few children went to school, particularly not poor children, so they learnt in other ways.

GRAHAM:

Good idea. What’s next?

CATHY:

Maybe Nicholas Nickleby. Actually he taught in a really cruel school, didn’t he?

GRAHAM:

That’s right. But there’s also the company of touring actors that Nicholas joins. We could do something on theatres and other amusements of the time. We don’t want only the bad things, do we?

GRAHAM:

What about Martin Chuzzlewit? He goes to the USA, doesn’t he?

CATHY:

Yes, and Dickens himself had been there a year before, and drew on his experience there in the novel.

GRAHAM:

I wonder, though … The main theme is selfishness, so we could do something on social justice? No, too general, let’s keep to your idea – I think it would work well.

CATHY:

He wrote Bleak House next – that’s my favourite of his novels.

GRAHAM:

Yes, mine too. His satire of the legal system is pretty powerful.

...:

CATHY: That’s true, but think about Esther, the heroine. As a child she lives with someone she doesn’t know is her aunt, who treats her very badly. Then she’s very happy living with her guardian, and he puts her in charge of the household.

...:

And at the end she gets married and her guardian gives her and her husband a house, where of course they’re very happy.

...:

GRAHAM: Yes, I like that.

...:

CATHY: What shall we take next? Little Dorrit? Old Mr Dorrit has been in a debtors’ prison for years …

...:

GRAHAM: So was Dicken’s father, wasn’t he?

...:

CATHY: That’s right.

...:

GRAHAM: What about focusing on the part when Mr Dorrit inherits a fortune, and he starts pretending he’s always been rich?

...:

GRAHAM: OK, so next we need to think about what materials we want to illustrate each issue. That’s going to be quite hard.

Sau khi nghe "have you gathered who’s expected to come and see the display?" là biết đáp án chuẩn bị vào.

Sau khi nghe "have you gathered who’s expected to come and see the display?" là biết đáp án chuẩn bị vào. Nhiều bạn khi nghe "Is it for the people studying English, or students from other departments?" thì chọn đáp án A (student from the English department).

Nhiều bạn khi nghe "Is it for the people studying English, or students from other departments?" thì chọn đáp án A (student from the English department). Sau đó nghe "It’ll be publicised in the city, to encourage people to come and find out something of what does on here"

Sau đó nghe "It’ll be publicised in the city, to encourage people to come and find out something of what does on here"