The future of the World's Language

Of the world’s 6,500 living languages, around half are expected to the out by the end of this century, according to UNESCO. Just 11 are spoken by more than half of the earth’s population, so it is little wonder that those used by only a few are being left behind as we become a more homogenous, global society. In short, 95 percent of the world’s languages are spoken by only five percent of its population—a remarkable level of linguistic diversity stored in tiny pockets of speakers around the world. Mark Turin, a university professor, has launched WOLP (World Oral Language Project) to prevent the language from the brink of extinction.

He is trying to encourage indigenous communities to collaborate with anthropologists around the world to record what he calls “oral literature” through video cameras, voice recorders and other multimedia tools by awarding grants from a £30,000 pot that the project has secured this year. The idea is to collate this literature in a digital archive that can be accessed on demand and will make the nuts and bolts of lost cultures readily available.

For many of these communities, the oral tradition is at the heart of their culture. The stories they tell are creative as well as communicative. Unlike the languages with celebrated written traditions, such as Sanskrit, Hebrew and Ancient Greek, few indigenous communities have recorded their own languages or ever had them recorded until now.

The project suggested itself when Turin was teaching in Nepal. He wanted to study for a PhD in endangered languages and, while discussing it with his professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, was drawn to a map on his tutor’s wall. The map was full of pins of a variety of colours which represented all the world’s languages that were completely undocumented. At random, Turin chose a “pin” to document. It happened to belong to the Thangmi tribe, an indigenous community in the hills east of Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. “Many of the choices of anthropologists and linguists who work on these traditional field-work projects are quite random,” he admits.

Continuing his work with the Thangmi community in the 1990s, Turin began to record the language he was hearing, realising that not only was this language and its culture entirely undocumented, it was known to few outside the tiny community. He set about trying to record their language and myth of origins. “I wrote 1,000 pages of grammar in English that nobody could use—but I realised that wasn’t enough. It wasn’t enough for me, it wasn’t enough for them. It simply wasn’t going to work as something for the community. So then I produced this trilingual word list in Thangmi, Nepali and English.”

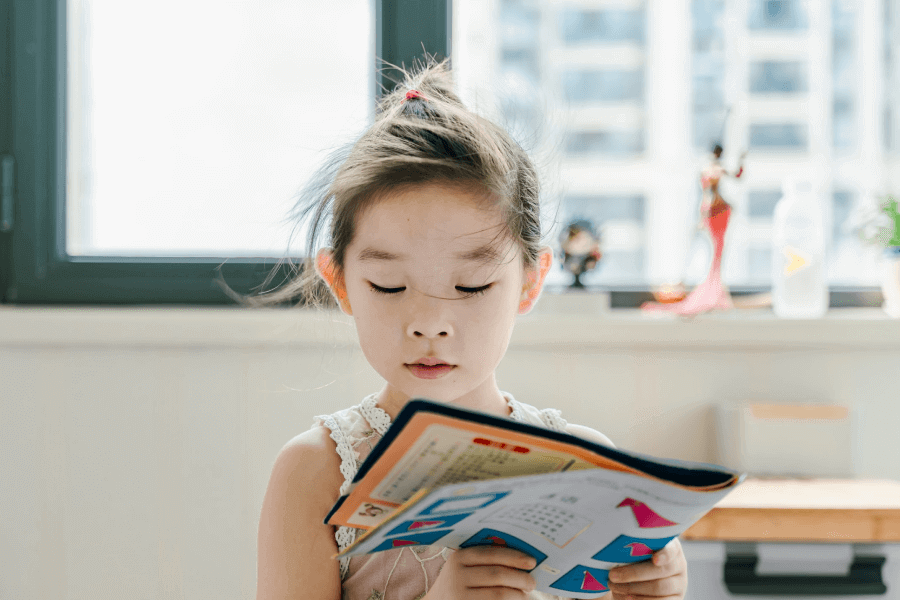

In short, it was the first ever publication of that language. That small dictionary is still sold in local schools for a modest 20 rupees, and used as part of a wider cultural regeneration process to educate children about their heritage and language. The task is no small undertaking: Nepal itself is a country of massive ethnic and linguistic diversity, home to 100 languages from four different language families. What’s more, even fewer ethnic Thangmi speak the Thangmi language. Many of the community members have taken to speaking Nepali, the national language taught in schools and spread through the media, and community elders are dying without passing on their knowledge.

Despite Turin’s enthusiasm for his subject, he is baffled by many linguists’ refusal to engage in the issue he is working on. “Of the 6,500 languages spoken on Earth, many do not have written traditions and many of these spoken forms are endangered,” he says. “There are more linguists in universities around the world than there are spoken languages—but most of them aren’t working on this issue. To me it’s amazing that in this day and age, we still have an entirely incomplete image of the world’s linguistic diversity. People do PhDs on the apostrophe in French, yet we still don’t know how many languages are spoken.”

“When a language becomes endangered, so too does a cultural world view. We want to engage with indigenous people to document their myths and folklore, which can be harder to find funding for if you are based outside Western universities.”

Yet, despite the struggles facing initiatives such as the World Oral Literature Project, there are historical examples that point to the possibility that language restoration is no mere academic pipe dream. The revival of a modern form of Hebrew in the 19th century is often cited as one of the best proofs that languages long dead, belonging to small communities, can be resurrected and embraced by a large number of people. By the 20th century, Hebrew was well on its way to becoming the main language of the Jewish population of both Ottoman and British Palestine. It is now spoken by more than seven million people in Israel.

Yet, despite the difficulties these communities face in saving their languages, Dr Turin believes that the fate of the world’s endangered languages is not sealed, and globalization is not necessarily the nefarious perpetrator of evil it is often presented to be. “I call it the globalisation paradox: on the one hand globalisation and rapid socio-economic change are the things that are eroding and challenging diversity. But on the other, globalisation is providing us with new and very exciting tools and facilities to get to places to document those things that globalisation is eroding. Also, the communities at the coal-face of change are excited by what globalisation has to offer.”

In the meantime, the race is on to collect and protect as many of the languages as possible, so that the Rai Shaman in eastern Nepal and those in the generations that follow him can continue their traditions and have a sense of identity. And it certainly is a race: Turin knows his project’s limits and believes it inevitable that a large number of those languages will disappear. “We have to be wholly realistic. A project like ours is in no position, and was not designed, to keep languages alive. The only people who can help languages survive are the people in those communities themselves. They need to be reminded that it’s good to speak their own language and I think we can help them do that—becoming modem doesn’t mean you have to lose your language.”

Áp dụng Linearthinking để nắm main idea:

Áp dụng Linearthinking để nắm main idea: