Homer’s Literary Legacy

Why was the work of Homer, famous author of ancient Greece, so full of clichés?

A

A. Until the last tick of history’s clock, cultural transmission meant oral transmission and poetry, passed from mouth to ear, was the principal medium of moving information across space and from one generation to the next. Oral poetry was not simply a way of telling lovely or important stories, or of flexing the imagination. It was, argues the classicist Eric Havelock, a “massive repository of useful knowledge, a sort of encyclopedia of ethics, politics, history and technology which the effective citizen was required to learn as the core of his educational equipment”. The great oral works transmitted a shared cultural heritage, held in common not on bookshelves, but in brains. In India, an entire class of priests was charged with memorizing the Vedas with perfect fidelity. In pre-lslamic Arabia, people known as Rawis were often attached to poets as official memorizers. The Buddha’s teachings were passed down in an unbroken chain of oral tradition for four centuries until they were committed to writing in Sri Lanka in the first century B.C.

B

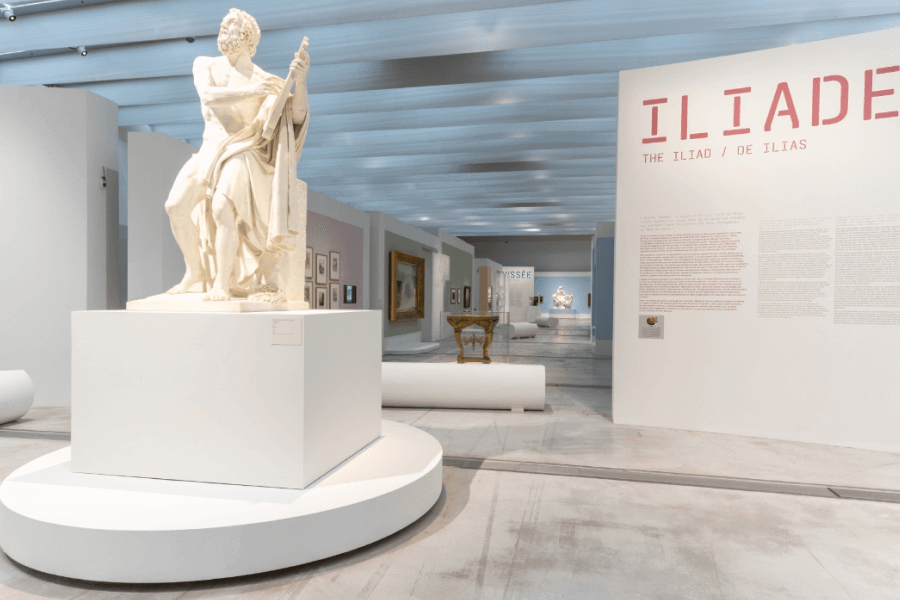

B. The most famous of the Western tradition’s oral works, and the first to have been systematically studied, were Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad. These two poems – possibly the first to have been written down in the Greek alphabet – had long been held up as literary archetypes. However, even as they were celebrated as the models to which all literature should aspire, Homer’s masterworks had also long been the source of scholarly unease. The earliest modern critics sensed that they were somehow qualitatively different from everything that came after – even a little strange. For one thing, both poems were oddly repetitive in the way they referred to characters. Odysseus was always “clever Odysseus”. Dawn was always “rosy-fingered”. Why would someone write that? Sometimes the epithets seemed completely off-key. Why call the murderer of Agamemnon “blameless Aegisthos”? Why refer to “swift-footed Achilles” even when he was sitting down? Or to “laughing Aphrodite” even when she was in tears? In terms of both structure and theme, the Odyssey and Iliad were also oddly formulaic, to the point of predictability. The same narrative units – gathering armies, heroic shields, challenges between rivals – pop up again and again, only with different characters and different circumstances. In the context of such finely spun, deliberate masterpieces, these quirks* seemed hard to explain.

C

C. At the heart of the unease about these earliest works of literature were two fundamental questions: first, how could Greek literature have been born ex nihilo* with two masterpieces? Surely a few less perfect stories must have come before, and yet these two were among the first on record. And second, who exactly was their author? Or was it authors? There were no historical records of Homer, and no trustworthy biography of the man exists beyond a few self-referential hints embedded in the texts themselves.

D

D. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was one of the first modern critics to suggest that Homer might not have been an author in the contemporary sense of a single person who sat down and wrote a story and then published it for others to read. In his 1781 Essay on the Origin of Languages, the Swiss philosopher suggested that the Odyssey and Iliad might have been “written only in men’s memories. Somewhat later they were laboriously collected in writing”- though that was about as far as his enquiry into the matter went.

E

E. In 1795, the German philologist Friedrich August Wolf argued for the first time that not only were Homer’s works not written down by Homer, but they weren’t even by Homer. They were, rather, a loose collection of songs transmitted by generations of Greek bards*, and only redacted* in their present form at some later date. In 1920, an eighteen-year-old scholar named Milman Parry took up the question of Homeric authorship as his Master’s thesis at the University of California, Berkeley. He suggested that the reason Homer’s epics seemed unlike other literature was because they were unlike other literature. Parry had discovered what Wood and Wolf had missed: the evidence that the poems had been transmitted orally was right there in the text itself. All those stylistic quirks, including the formulaic and recurring plot elements and the bizarrely repetitive epithets -“clever Odysseus” and “gray-eyed Athena”- that had always perplexed readers were actually like thumbprints left by a potter: material evidence of how the poems had been crafted. They were mnemonic* aids that helped the bard(s) fit the meter and pattern of the line, and remember the essence of the poems.

F

F. The greatest author of antiquity was actually, Parry argued, just “one of a long tradition of oral poets that… composed wholly without the aid of writing”. Parry realised that if you were setting out to create memorable poems, the Odyssey and the Iliad were exactly the kind of poems you’d create. It’s said that cliches* are the worst sin a writer can commit, but to an oral bard, they were essential. The very reason that cliches so easily seep into our speech and writing – their insidious memorability – is exactly why they played such an important role in oral story telling. The principles that the oral bards discovered as they sharpened their stories through telling and retelling were the same mnemonic principles that psychologists rediscovered when they began conducting their first scientific experiments on memory around the turn of the twentieth century.

Words that rhyme are much more memorable than words that don’t, and concrete nouns are easier to remember than abstract ones. Finding patterns and structure in information is how our brains extract meaning from the world, and putting words to music and rhyme is a way of adding extra levels of pattern and structure to language.

BƯỚC 1: Đọc câu hỏi để hiểu rõ.

BƯỚC 1: Đọc câu hỏi để hiểu rõ. BƯỚC 2: Xác định thông tin liên quan.

BƯỚC 2: Xác định thông tin liên quan.